NBWC 2021 Program

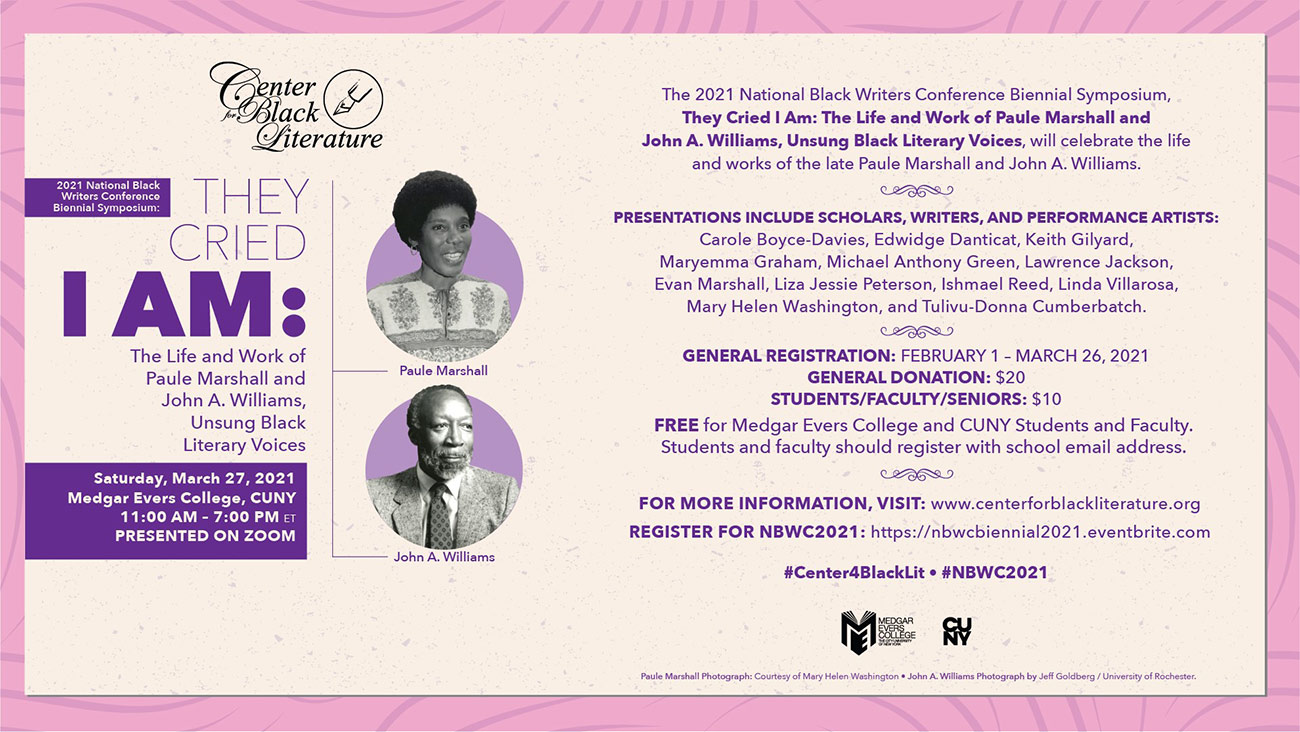

“They Cried I Am: The Life and Work of Paule Marshall and John A. Williams, Unsung Black Literary Voices”

Saturday, March 27, 2021

11:00 a.m. - 7:00 p.m. ET

Presented Virtually (via Zoom)

The 2021 National Black Writers Conference Biennial Symposium, “They Cried I Am: The Life and Work of Paule Marshall and John A. Williams, Unsung Black Literary Voices,” will celebrate the life and works of the late Paule Marshall and the late John A. Williams.

Featured program highlights will include a keynote address, roundtable discussions, and dramatic readings. Confirmed speakers include Carole Boyce-Davies, Edwidge Danticat, Keith Gilyard, Maryemma Graham, Michael Anthony Green, Lawrence Jackson, Evan Marshall, Liza Jessie Peterson, Ishmael Reed, Linda Villarosa, Mary Helen Washington, Adam Williams, and Jamia Wilson.

Tulivu-Donna Cumberbatch and Seasoned Elegance will offer a special jazz performance.

NBWC2021 Speakers and Participants

(click picture to see bio)

Carole Boyce-Davies

Tulivu-Donna Cumberbatch

Edwidge Danticat

Wallace L. Ford

Maryemma Graham

Keith Gilyard

Michael Anthony Green

Donna Hill

Lawrence P. Jackson

Evan Marshall

Liza Jessie Peterson

Ishmael Reed

Linda Villarosa

Mary Helen Washington

Jamia Wilson

NBWC2021 Honorees

Paule Marshall (1929–2019)

Paule Marshall, who died August 12, 2019, at age 90, played an indispensable role in the shaping of twentieth- and twenty-first century African American and African diaspora literary canons and in making Black women central to those traditions. Writer Alice Walker described Marshall as a writer “unequaled in intelligence, vision, craft, by anyone of her generation.” Marshall’s 1959 novel Brown Girl, Brownstones is hailed in the Norton Anthology of African American Literature as “the novel that most Black feminist critics consider to be the beginning of contemporary African American women’s writings.” In all of her fiction, Marshall produced Black women figures that are creative, daring, and intelligent, traveling the world in search of an expansive sense of Black identity and community. Marshall’s published work spans five decades: Brown Girl, Brownstones, 1959; Soul Clap Hands and Sing, 1961, The Chosen Place, The Timeless People, 1969; Reena and Other Stories, 1983; Praisesong for the Widow, 1983; Daughters, 1991; The Fisher King, 2000; and she published a memoir, Triangular Road, in 2009.

Paule Marshall, who died August 12, 2019, at age 90, played an indispensable role in the shaping of twentieth- and twenty-first century African American and African diaspora literary canons and in making Black women central to those traditions. Writer Alice Walker described Marshall as a writer “unequaled in intelligence, vision, craft, by anyone of her generation.” Marshall’s 1959 novel Brown Girl, Brownstones is hailed in the Norton Anthology of African American Literature as “the novel that most Black feminist critics consider to be the beginning of contemporary African American women’s writings.” In all of her fiction, Marshall produced Black women figures that are creative, daring, and intelligent, traveling the world in search of an expansive sense of Black identity and community. Marshall’s published work spans five decades: Brown Girl, Brownstones, 1959; Soul Clap Hands and Sing, 1961, The Chosen Place, The Timeless People, 1969; Reena and Other Stories, 1983; Praisesong for the Widow, 1983; Daughters, 1991; The Fisher King, 2000; and she published a memoir, Triangular Road, in 2009.

She was born Valenza Pauline Burke in Brooklyn in 1929, the daughter of Barbadian immigrants, Adriana and Samuel Burke. A brilliant student, Marshall graduated as salutatorian of her high school class at Brooklyn’s Bushwick High School. In 1946, she was accepted at Hunter College but left in 1948 when she fell ill with tuberculosis. After her recovery, she enrolled at Brooklyn College, graduating cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa in 1952. Thinking that her name Pauline would discourage her job prospects in journalism, she changed her name to Paule, with a silent “e,” always insisting that her name be pronounced “Paule—like a man.” After college, she worked at Our World magazine with editor John P. Davis, who sent her to South America and the Caribbean to represent the magazine. She married sociologist Dr. Kenneth Marshall in 1950. They had a son Evan Keith in 1959 and were divorced in 1963. She married Haitian businessman Nourry Menard in 1970 and lived for part of each year in Haiti. They were divorced in 1985.

In the 1960s, Marshall, along with Lorraine Hansberry, Alice Childress, and Sarah E. Wright, was a member of the panel on “The Negro Woman and American Literature,” which began the groundbreaking work of critiquing and challenging stereotypes about Black women. As a member of the Association of Artists for Freedom, she explicitly endorsed Black nationalist rhetoric, calling for “the rise through revolutionary struggle of the darker peoples of the world.” Embracing her identity as a writer of the African diaspora, Marshall defined herself as “West Indian, by heritage,” and “solidly Afro-American by birth,” and always placed her characters and her readers in diasporan worlds. She lived and wrote for a time in Barbados, Grenada, and Haiti. As she traveled back and forth across oceans, from the United States to the West Indies to Africa, Marshall was always politically active—from the civil rights movement and Black nationalist movements in the U.S., to West Indian independence movements, and the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. Whether her fiction is set in the U.S. or in the Caribbean, Marshall stages the personal struggles of her characters against the oppressive hierarchies of gender, race, sexuality, and colonialism.

Paule Marshall was awarded a Guggenheim in 1961; the John Dos Passos Award for Literature in 1989; a MacArthur Fellowship in 1992; the Anisfield-Wolf Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010; and the Virginia Commonwealth University Distinguished Artist/Scholar Award in 1994. In 2017, she was given a lifetime achievement award in Barbados for her work and activism there. Marshall taught creative writing at Columbia University, University of California, Berkeley, Yale University, and Virginia Commonwealth University. In her position as Helen Gould Sheppard Chair of Literature and Culture at New York University from 1995 until 2009, she established The New Generation Series in order to showcase younger Black writers from the U.S., Africa, and the Caribbean. — Biography by Mary Helen Washington. Photograph Courtesy Mary Helen Washington

John Alfred Williams (1925–2015)

John Alfred Williams was born in Jackson, Mississippi, and raised in Syracuse, New York. He joined the U.S. Navy in 1943, serving as a pharmacist’s mate in the South Pacific, and attended Syracuse University on the G.I. Bill, graduating with a degree in English and journalism in 1950. Married with two sons, he worked at various jobs to make ends meet. Between separation and divorce, Williams moved to Los Angeles, where he worked briefly in insurance and television publicity before returning to the East Coast. He then worked for a vanity press in Manhattan, where he met Lorrain Isaac, who became his second wife and mother of his third son. After working in radio, for the American Committee on Africa, and on journalism assignments abroad, he published his first novel, The Angry Ones (1960), a.k.a. One for New York.

Williams had one of the most prolific careers in twentieth-century American letters. He is perhaps best known for The Man Who Cried I Am (1967), a novel about a dying African American writer in Europe who learns of the “King Alfred Plan,” a government plot to eliminate Black unrest in America. Other novels include Night Song (1961), Sissie (1963), Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light (1969), Captain Blackman (1972), Mothersill and the Foxes (1975), The Junior Bachelor Society (1976), !Click Song (1982), The Berhama Account (1985), and Jacob’s Ladder (1987). His last published novel, Clifford’s Blues (1999)—the diary of a Black, gay, jazz pianist in Dachau—may be his finest achievement. Williams also published numerous short stories, a play, a volume of poetry, and wrote the libretto to the opera Vanqui.

Williams’s career is distinguished further by his work in nonfiction, such as The King God Didn’t Save (1970), a controversial analysis of the government agencies and media apparatus surrounding Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Other notables include The Most Native of Sons: A Biography of Richard Wright (1970) for young adult readers, and If I Stop, I’ll Die: The Comedy and Tragedy of Richard Pryor (1991), co-written with his son Dennis. Williams also authored the children’s book Africa, Her History, Lands, and People (1963) and the American travelogue This Is My Country Too (1965). He co-edited Amistad 1 and 2, volumes of contemporary writing, and Dear Chester, Dear John (2008), a collection of letters between himself and author Chester Himes. Williams also published extensively as a journalist, appearing in the Los Angeles Times, The Nation, Holiday, Newsweek, Ebony, Jet, and more.

These accomplishments were recognized by numerous awards, including Syracuse University’s Centennial Medal for Outstanding Achievement (1970), the Richard Wright—Jacques Roumain Award (1973), a National Endowment for the Arts grant (1977), a New Jersey State Council on the Arts Award (1985), and the Before Columbus Foundation’s American Book Award in 1983 and 1998. Williams also received honorary degrees from numerous universities, including the University of Rochester in 2003.

Williams taught at a variety of institutions, including LaGuardia Community College, Boston University, and NYU. In 1994, he retired from Rutgers University, Newark, where he had been a professor of English, journalism, and creative writing since 1979. At Rutgers, he earned the Lindback Award for Distinguished Teaching in 1982 and was named Paul Robeson Distinguished Professor of English in 1990. In the early 2000s, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, which led to hospitalization at a Veterans Administration facility in Paramus, New Jersey, where he died in 2015.

Williams’s works “dispel(led) common myths and misunderstandings about black Americans.”1 He asserted not only Black cultural specificity and the radical demands of Black Power, but also that African American literature transcended racial difference. He criticized “the ghetto-ization of Black writers,” insisting that they be reviewed and taught alongside non-Black writers. Acknowledging the multiplicity of Black experiences, Williams said, “We must accept difference–celebrate it. We’re not a monolith–one thing.”2 James DeJongh called Williams “arguably the finest Afro-American novelist of his generation.”3 Exceptional productivity, undeniable storytelling skills, and compelling affirmations of the humanity and diversity of Black people made John A. Williams a figure to be emulated by African American writers of subsequent generations as well.

- James DeJongh, “John A. Williams” Dictionary of Literary Biography, 33 (1984) 268

- Qtd. In Fleming

- DeJongh 280

– Biography by Jeffrey Allen Tucker, February 2021

Jeffrey Allen Tucker is an associate professor in the Department of English at the University of Rochester. He is author of A Sense of Wonder: Samuel R. Delany, Race, Identity, & Difference (Wesleyan, 2004), editor of Conversations with John A. Williams (Mississippi, 2018), and co-editor of Race Consciousness: African American Studies for the New Century (NYU, 1997), as well as the author of articles on writers such as Octavia E. Butler, George S. Schuyler, and Colson Whitehead.

Photograph Courtesy of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester.

Contact Us

Center for Black Literature (CBL)

at Medgar Evers College, CUNY

1534 Bedford Avenue | 2nd Floor

Brooklyn, New York 11216

(Click HERE for the Postal Mailing Address)

Main Phone: (718) 804-8884

Main Office: info@centerforblackliterature.org

Donate to CBL Today!

To carry out our literary programs and special events, we depend on financial support from the public. Donations are welcome year-round. Please click HERE to donate. Thank you!

...

The Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College is supported in part by an American Rescue Plan Act grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to support general operating expenses in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

We're Where You Are!

Get The Latest News!

Sign-up to receive news about our programs!

Copyright © 2023, Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College.