By Tracey Squires.

My black body is a playground,

My arms, swings to swing on

My torso, a sloping slide for you to slide down,

You leave your footprints in my sandbox.

– (poem by the author)

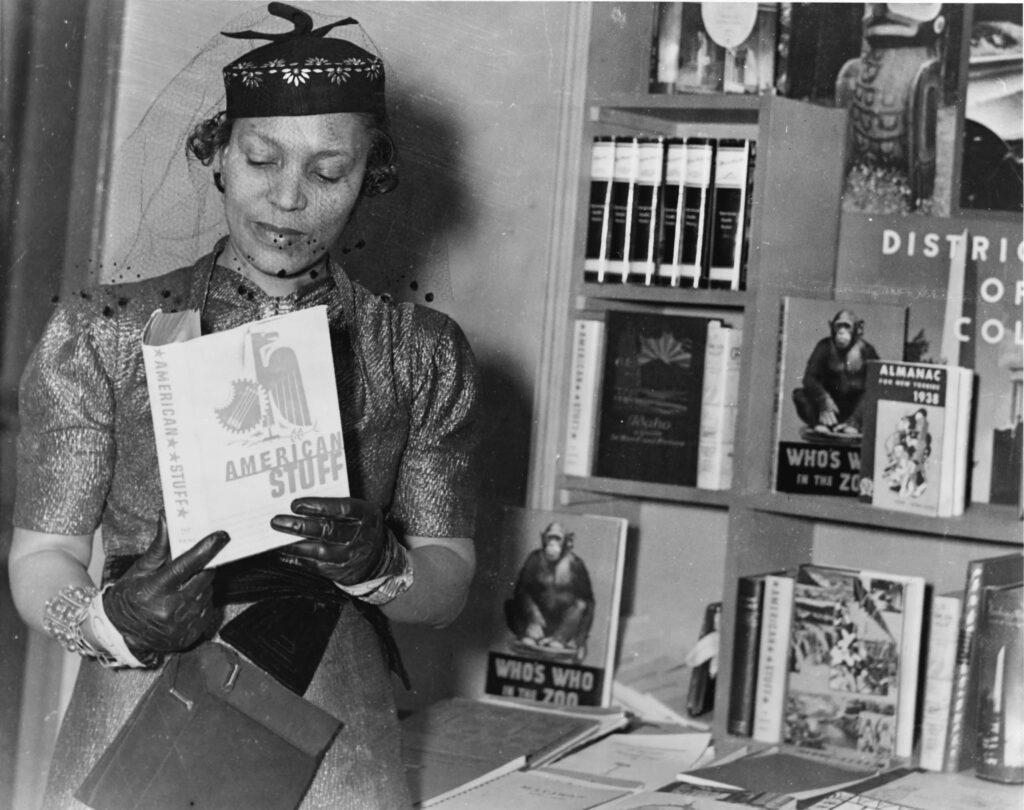

Chartering a conversation on the demonization of the Black woman’s body, authors like Toni Morrison and Zora Neal Hurston foreground the dialectic of sexuality and Black feminist literature. Pervading characters like Morrison’s Sula and Hurston’s Janie is a concept of the Black woman as an agent of her own body and, moreover, as an enactor of her autonomy. Black Feminist literature gives characters like these a space to thrive in and grants their authors the license to write them. One should acknowledge, however, that it is the genre of Black literature that facilitates the existence of feminist discourse. We have not always had this space to celebrate Black writers, and even less Black women writers. Before Hurston, there was Richard Wright and, before him, the literature that represented Black personhood was often slave narratives. These accounts, while effective in achieving what they sought to do, failed to include much of the Black experience. We do not experience the Black woman fully existing within an autonomous identity, and one can entirely understand the reason why. It was a vastly different time, and these authors wrote the facets of their experience that they thought they were allowed to tell. Hurston made a gamble and ventured to write beyond her time. As a Black woman writer in the 1830s, she flung into existence a character that defied every parameter set for the Black woman. Their Eyes Were Watching God was not received kindly, either in her lifetime or in that of her son. I believe this reception was largely due to the paucity of Black Literature, especially that of Black Feminist discourses. There was no support for Hurston because there was no genre or literary space ready to receive her work. No one granted her a license to write Janie – a Black feminist woman character who also basked in her own sexuality. Hurston ventured off into the unknown and bled with her words a song sung over a silence long held. We need Black Literature to ensure that we will never have a repeat of Hurston’s story. How cold was her welcome as a writer when she simply wrote the truth! Hurston died in poverty, her book out of print and dismissed as a work “cloaked in sensuality.” However, with this, one must ask, why was it so disturbing to see the Black woman exercising her autonomy?

Both Hurston’s Janie and Morrison’s Sula, as characters, directly oppose a system that for so long had been set in stone. This system was birthed through the Transatlantic slave trade where the bodies of Black women were demonized and made inhumane. Society has attached a primitive connotation to the Black woman’s body, . There is a prodigious objectification that occurs with her sexuality and when she exercises agency and says, “this is mine, this is mine to use as I see fit,” she demands her humanity and collapses a system that has been rigged against her. Author Brittney Cooper speaks on this as the silencing of sexuality and advocates the need for us to politicize pleasure. Hurston’s Janie and Morrison’s Sula are both ostracized by a society that has been conditioned to view the Black woman a certain way. As they both choose to take ownership of their sexuality, we see this desire from the world for “secrecy”. Their stories told from their mouths, in their own language, exercising their agency, go against what our conditioned system of thought has connoted the Black woman’s body to be. For us to write authentically, we must have genres like Black Feminist Literature, ready and willing to receive our work.

Tracey Squires is a senior at Medgar Evers College; her major is English and Cross-Cultural Literature. When she is not immersed in a good book, you can find her exploring the wonders of the natural world.